☝️🤓 First off, Z-order curves have nothing to do with rendering order or Z-depth.

Rather, such a “curve” is a useful mathematical tool for calculating a value, or code, for some entity, such as a point or a triangle, which approximates the relative position of that entity within some spatial grid. Entities which are closer together in space will have closer values, and entities which are far away from each other will have a greater difference in their calculated value.

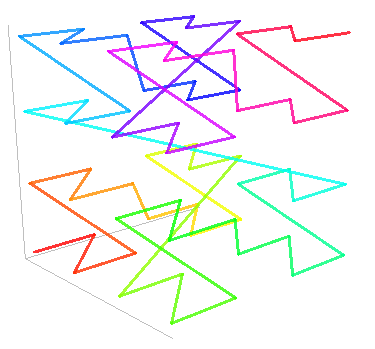

The Z-order curve is named the way that it is because each successive code in the sequence takes a zigzagging, Z-shaped path. Sometimes the Z-order curve value is referred to as a Morton code.

Z-order curves provide an effective way to sort points, triangles, or other spatially located items in N-dimensional-space such that they fill space efficiently in an ordered way. For example, all of the triangles which are spatially near each other in 3D space will have a tendency to be near each other along a Z-order curve, and so it provides an effective way of packing points and triangles based on how close they are to each other.

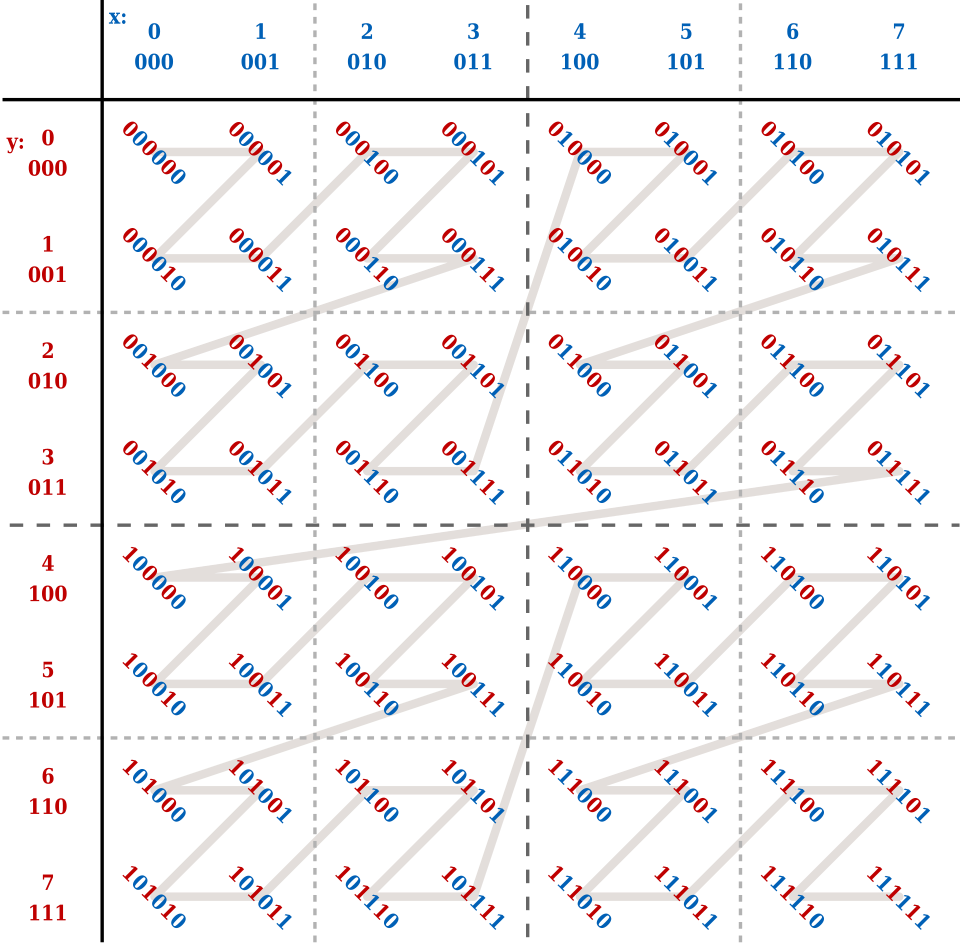

The diagram below demonstrates how a Z-order curve works in 2D.

Essentially, for a given XY integer coordinate, we take the binary representation of the X component, and the Y component, and then we interleave them together in order to get the resulting Z-order curve value.

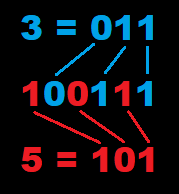

For example, take the case where we have an 8×8, 2D grid. We have a point in the grid which we have determined falls within cell (3,5), so X=3 (011) and Y=5 (101).

To get a Z-order value, we need to interleave our binary X and Y values. So we take the lowest order bit of the X value and use it as the first (lowest order) bit of our binary Z-order curve value. For the next bit, we take the lowest order bit of the Y value. We then go back to the X value, but we take the next bit, then swap back to Y, etc., until we have our number.

After we interleave, we end up with a result of 100111 in binary, which is 39 in decimal. Imagine that we have 1 point within each cell of our 8×8 grid. Once we have computed Z-order curve values for each point and sorted them from lowest to highest, our point (which has a value of 39) would be 40th in the list (don’t forget to count 0!). And if you look at the picture of a 6-bit Z-order curve above, you can see that if you count to the 40th position along it, the value is indeed 100111.

If we have a 6-bit number, and we’re encoding 2 dimensions (X and Y) into our Z-order curve value, we can represent 8 possible coordinates along each axis, since we have 3 bits per axis, and with 3 bits we can represent the numbers 0-7.

For 3D, we use the same process, but we have to interleave our Z coordinate as well, so after we add each Y coordinate bit, the next highest order bit in our Z-order curve value will be a bit from our calculated Z coordinate.

In 3D, it’s common to use a 32-bit integer to store a Z-order curve value. So that gives us 10 bits each, or 210 (1024) possible coordinates in each dimension (X, Y, and Z), since we have 30 bits available for 3D coordinate representation. If you really wanted to, you could encode an additional two values into the remaining 2 bits, giving you 2048 possible coordinates in both the X and Y dimensions (or however you wanna slice it), but we’re not gonna do that here. We’ll just leave the other 2 bits for our critter friends to chew on. 🐇🐿️

The Z-Order Curve Value Computation Algorithm

The general algorithm to determine the Z-order curve value for a 3D coordinate looks like this:

//The bounding box is the 3D area all of our positions should fall into.

//It isn't necessary to use a bounding box structure, but for the sake of

//simplicity, rather than passing in minimum and maximum X, Y, and

//Z values, it's recommended.

public uint GetZCurveValue(float3 point, BoundingBox bbox)

{

uint result = 0;

//Determine the normalized position of our point within

//the bounded area (between 0.0 and 1.0)

//We clamp the value to make sure that we stay within our

//possible coordinate range (0-1024)

float3 normalizedPos = clamp((point - bbox.min) / (bbox.max - bbox.min), 0f, 0.999999f);

//Assuming a 32 bit return value, we have 2^10 possibilities per dimension.

//Calculate the approximate cell (out of 1024 in each dimension)

uint3 xyzCell = (uint3)(normalizedPos * 1023);

//Loop through all 10 bits of the X, Y, and Z value and interleave them

//into a single 32-bit int

int offset = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

//Perform bitwise operations to interleave the values

//First, shift each value to the right by i bits, then perform a bitwise AND with 1

//Then shift the 1 or 0 to the left by the current number of offset bits

//Finally, perform a bitwise OR to combine it with the result up to this point.

result |= ((xyzCell.x >> i) & 1) << offset;

result |= ((xyzCell.y >> i) & 1) << (offset + 1);

result |= ((xyzCell.z >> i) & 1) << (offset + 2);

//Increment the offset by 3 so we can move to the next 3 interleaved bits

offset += 3;

}

return result;

}While this algorithm may be sufficient, there is an optimization which improves the speed by around 5-10x by using specific bit operations:

public uint GetZCurveValue(float3 point, BoundingBox bbox)

{

float3 normalizedPos = clamp((point- bbox.min) / (bbox.max - bbox.min), 0f, 0.999999f);

uint3 xyzCell = (uint3)(normalizedPos * 1023);

//Call the GetZCurveBitCoordinate function for each dimension, then

//interleave the results by shifting the Y result over by 1 bit, and shifting

//the Z result by two bits.

return GetZCurveBitCoordinate(xyzCell.x) |

(GetZCurveBitCoordinate(xyzCell.y) << 1) |

(GetZCurveBitCoordinate(xyzCell.z) << 2);

}

//Sequentially shifts the bits of the provided one-dimensional coordinate

//until each representative bit is separated from all of the other bits using two zeros.

public uint GetZCurveBitCoordinate(uint value)

{

value &= 0x000003FF; //00000000000000000000001111111111

value = (value | (value << 16)) & 0x030000FF; //00000011000000000000000011111111

value = (value | (value << 8)) & 0x0300F00F; //00000011000000001111000000001111

value = (value | (value << 4)) & 0x030C30C3; //00000011000011000011000011000011

value = (value | (value << 2)) & 0x09249249; //00001001001001001001001001001001

return value;

}Once we’ve computed Z-order curve values for points, triangles, or anything else, we have a way to sort things and linearly search through them in an efficient way. The Z-order curve is great for building quadtrees, octrees, and other data structures.